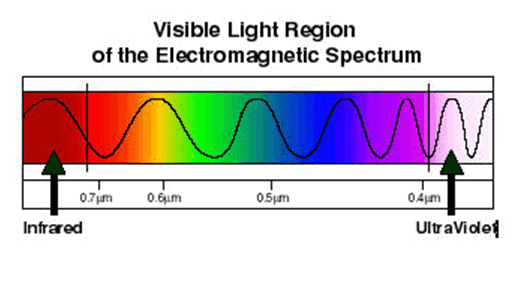

One of the central concepts in spectroscopy is a resonance and its corresponding resonant frequency. Resonances were first characterized in mechanical systems such as pendulums. Mechanical systems that vibrate or oscillate will experience large amplitude oscillations when they are driven at their resonant frequency. A plot of amplitude vs. excitation frequency will have a peak centered at the resonance frequency. This plot is one type of spectrum, with the peak often referred to as a spectral line, and most spectral lines have a similar appearance.

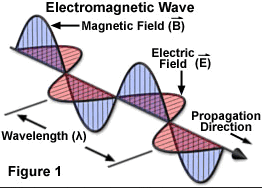

In quantum mechanical systems, the analogous resonance is a coupling of two quantum mechanical stationary states of one system, such as an atom, via an oscillatory source of energy such as a photon. The coupling of the two states is strongest when the energy of the source matches the energy difference between the two states. The energy (E) of a photon is related to its frequency (\nu) by E = h\nu where h is Planck's constant, and so a spectrum of the system response vs. photon frequency will peak at the resonant frequency or energy. Particles such as electrons and neutrons have a comparable relationship, the de Broglie relations, between their kinetic energy and their wavelength and frequency and therefore can also excite resonant interactions.

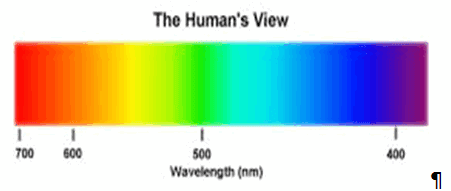

Spectra of atoms and molecules often consist of a series of spectral lines, each one representing a resonance between two different quantum states. The explanation of these series, and the spectral patterns associated with them, were one of the experimental enigmas that drove the development and acceptance of quantum mechanics. The hydrogen spectral series in particular was first successfully explained by the Rutherford-Bohr quantum model of the hydrogen atom. In some cases spectral lines are well separated and distinguishable, but spectral lines can also overlap and appear to be a single transition if the density of energy states is high enough.

In quantum mechanical systems, the analogous resonance is a coupling of two quantum mechanical stationary states of one system, such as an atom, via an oscillatory source of energy such as a photon. The coupling of the two states is strongest when the energy of the source matches the energy difference between the two states. The energy (E) of a photon is related to its frequency (\nu) by E = h\nu where h is Planck's constant, and so a spectrum of the system response vs. photon frequency will peak at the resonant frequency or energy. Particles such as electrons and neutrons have a comparable relationship, the de Broglie relations, between their kinetic energy and their wavelength and frequency and therefore can also excite resonant interactions.

Spectra of atoms and molecules often consist of a series of spectral lines, each one representing a resonance between two different quantum states. The explanation of these series, and the spectral patterns associated with them, were one of the experimental enigmas that drove the development and acceptance of quantum mechanics. The hydrogen spectral series in particular was first successfully explained by the Rutherford-Bohr quantum model of the hydrogen atom. In some cases spectral lines are well separated and distinguishable, but spectral lines can also overlap and appear to be a single transition if the density of energy states is high enough.

0 comments:

Post a Comment